See yesterday's stories here below.

April 2007

by John Bellamy Foster

Changes in capitalism over the last three decades have been commonly characterized using a trio of terms: neoliberalism, globalization, and financialization. Although a lot has been written on the first two of these, much less attention has been given to the third.1 Yet, financialization is now increasingly seen as the dominant force in this triad. The financialization of capitalism—the shift in gravity of economic activity from production (and even from much of the growing service sector) to finance—is thus one of the key issues of our time. More than any other phenomenon it raises the question: has capitalism entered a new stage?

I will argue that although the system has changed as a result of financialization, this falls short of a whole new stage of capitalism, since the basic problem of accumulation within production remains the same. Instead, financialization has resulted in a new hybrid phase of the monopoly stage of capitalism that might be termed “monopoly-finance capital.”2 Rather than advancing in a fundamental way, capital is trapped in a seemingly endless cycle of stagnation and financial explosion. These new economic relations of monopoly-finance capital have their epicenter in the United States, still the dominant capitalist economy, but have increasingly penetrated the global system.

The origins of the term “financialization” are obscure, although it began to appear with increasing frequency in the early 1990s.3 The fundamental issue of a gravitational shift toward finance in capitalism as a whole, however, has been around since the late 1960s. The earliest figures on the left (or perhaps anywhere) to explore this question systematically were Harry Magdoff and Paul Sweezy, writing for Monthly Review.4

As Robert Pollin, a major analyst of financialization who teaches economics at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, has noted: “beginning in the late 1960s and continuing through the 1970s and 1980s” Magdoff and Sweezy documented “the emerging form of capitalism that has now become ascendant—the increasing role of finance in the operations of capitalism. This has been termed ‘financialization,’ and I think it’s fair to say that Paul and Harry were the first people on the left to notice this and call attention [to it]. They did so with their typical cogency, command of the basics, and capacity to see the broader implications for a Marxist understanding of reality.” As Pollin remarked on a later occasion: “Harry [Magdoff] and Paul Sweezy were true pioneers in recognizing this trend....[A] major aspect of their work was the fact that these essays [in Monthly Review over three decades] tracked in simple but compelling empirical detail the emergence of financialization as a phenomenon....It is not clear when people on the left would have noticed and made sense of these trends without Harry, along with Paul, having done so first.”5

From Stagnation to Financialization

In analyzing the financialization of capitalism, Magdoff and Sweezy were not mere chroniclers of a statistical trend. They viewed this through the lens of a historical analysis of capitalist development. Perhaps the most succinct expression of this was given by Sweezy in 1997, in an article entitled “More (or Less) on Globalization.” There he referred to what he called “the three most important underlying trends in the recent history of capitalism, the period beginning with the recession of 1974–75: (1) the slowing down of the overall rate of growth, (2) the worldwide proliferation of monopolistic (or oligipolistic) multinational corporations, and (3) what may be called the financialization of the capital accumulation process.”

For Sweezy these three trends were “intricately interrelated.” Monopolization tends to swell profits for the major corporations while also reducing “the demand for additional investment in increasingly controlled markets.” The logic is one of “more and more profits, fewer and fewer profitable investment opportunities, a recipe for slowing down capital accumulation and therefore economic growth which is powered by capital accumulation.”

The resulting “double process of faltering real investment and burgeoning financialization” as capital sought to find a way to utilize its economic surplus, first appeared with the waning of the “‘golden age’ of the post-Second World War decades and has persisted,” Sweezy observed, “with increasing intensity to the present.”6

This argument was rooted in the theoretical framework provided by Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy’s Monopoly Capital (1966), which was inspired by the work of economists Michal Kalecki and Josef Steindl—and going further back by Karl Marx and Rosa Luxemburg.7 The monopoly capitalist economy, Baran and Sweezy suggested, is a vastly productive system that generates huge surpluses for the tiny minority of monopolists/oligopolists who are the primary owners and chief beneficiaries of the system. As capitalists they naturally seek to invest this surplus in a drive to ever greater accumulation. But the same conditions that give rise to these surpluses also introduce barriers that limit their profitable investment. Corporations can just barely sell the current level of goods to consumers at prices calibrated to yield the going rate of oligopolistic profit. The weakness in the growth of consumption results in cutbacks in the utilization of productive capacity as corporations attempt to avoid overproduction and price reductions that threaten their profit margins. The consequent build-up of excess productive capacity is a warning sign for business, indicating that there is little room for investment in new capacity.

For the owners of capital the dilemma is what to do with the immense surpluses at their disposal in the face of a dearth of investment opportunities. Their main solution from the 1970s on was to expand their demand for financial products as a means of maintaining and expanding their money capital. On the supply side of this process, financial institutions stepped forward with a vast array of new financial instruments: futures, options, derivatives, hedge funds, etc. The result was skyrocketing financial speculation that has persisted now for decades.

Among orthodox economists there were a few who were concerned early on by this disproportionate growth of finance. In 1984 James Tobin, a former member of Kennedy’s Council of Economic Advisers and winner of the Nobel Prize in economics in 1981, delivered a talk “On the Efficiency of the Financial System” in which he concluded by referring to “the casino aspect of our financial markets.” As Tobin told his audience:

I confess to an uneasy Physiocratic suspicion...that we are throwing more and more of our resources...into financial activities remote from the production of goods and services, into activities that generate high private rewards disproportionate to their social productivity. I suspect that the immense power of the computer is being harnessed to this ‘paper economy,’ not to do the same transactions more economically but to balloon the quantity and variety of financial exchanges. For this reason perhaps, high technology has so far yielded disappointing results in economy-wide productivity. I fear that, as Keynes saw even in his day, the advantages of the liquidity and negotiability of financial instruments come at the cost of facilitating nth-degree speculation which is short-sighted and inefficient....I suspect that Keynes was right to suggest that we should provide greater deterrents to transient holdings of financial instruments and larger rewards for long-term investors.8

Tobin’s point was that capitalism was becoming inefficient by devoting its surplus capital increasingly to speculative, casino-like pursuits, rather than long-term investment in the real economy.9 In the 1970s he had proposed what subsequently came to be known as the “Tobin tax” on international foreign exchange transactions. This was designed to strengthen investment by shifting the weight of the global economy back from speculative finance to production.

In sharp contrast to those like Tobin who suggested that the rapid growth of finance was having detrimental effects on the real economy, Magdoff and Sweezy, in a 1985 article entitled “The Financial Explosion,” claimed that financialization was functional for capitalism in the context of a tendency to stagnation:

Does the casino society in fact channel far too much talent and energy into financial shell games. Yes, of course. No sensible person could deny it. Does it do so at the expense of producing real goods and services? Absolutely not. There is no reason whatever to assume that if you could deflate the financial structure, the talent and energy now employed there would move into productive pursuits. They would simply become unemployed and add to the country’s already huge reservoir of idle human and material resources. Is the casino society a significant drag on economic growth? Again, absolutely not. What growth the economy has experienced in recent years, apart from that attributable to an unprecedented peacetime military build-up, has been almost entirely due to the financial explosion.10

In this view capitalism was undergoing a transformation, represented by the complex, developing relation that had formed between stagnation and financialization. Nearly a decade later in “The Triumph of Financial Capital” Sweezy declared:

I said that this financial superstructure has been the creation of the last two decades. This means that its emergence was roughly contemporaneous with the return of stagnation in the 1970s. But doesn’t this fly in the face of all previous experience? Traditionally financial expansion has gone hand-in-hand with prosperity in the real economy. Is it really possible that this is no longer true, that now in the late twentieth century the opposite is more nearly the case: in other words, that now financial expansion feeds not on a healthy real economy but on a stagnant one?

The answer to this question, I think, is yes it is possible, and it has been happening. And I will add that I am quite convinced that the inverted relation between the financial and the real is the key to understanding the new trends in the world [economy].

In retrospect, it is clear that this “inverted relation” was a built-in possibility for capitalism from the start. But it was one that could materialize only in a definite stage of the development of the system. The abstract possibility lay in the fact, emphasized by both Marx and Keynes, that the capital accumulation process was twofold: involving the ownership of real assets and also the holding of paper claims to those real assets. Under these circumstances the possibility of a contradiction between real accumulation and financial speculation was intrinsic to the system from the start.

Although orthodox economists have long assumed that productive investment and financial investment are tied together—working on the simplistic assumption that the saver purchases a financial claim to real assets from the entrepreneur who then uses the money thus acquired to expand production—this has long been known to be false. There is no necessary direct connection between productive investment and the amassing of financial assets. It is thus possible for the two to be “decoupled” to a considerable degree.11 However, without a mature financial system this contradiction went no further than the speculative bubbles that dot the history of capitalism, normally signaling the end of a boom. Despite presenting serious disruptions, such events had little or no effect on the structure and function of the system as a whole.

It took the rise of monopoly capitalism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and the development of a market for industrial securities before finance could take center-stage, and before the contradiction between production and finance could mature. In the opening decades of the new regime of monopoly capital, investment banking, which had developed in relation to the railroads, emerged as a financial power center, facilitating massive corporate mergers and the growth of an economy dominated by giant, monopolistic corporations. This was the age of J. P. Morgan. Thorstein Veblen in the United States and Rudolf Hilferding in Austria both independently developed theories of monopoly capital in this period, emphasizing the role of finance capital in particular.

Nevertheless, when the decade of the Great Depression hit, the financial superstructure of the monopoly capitalist economy collapsed, marked by the 1929 stock market crash. Finance capital was greatly diminished in the Depression and played no essential role in the recovery of the real economy. What brought the U.S. economy out of the Depression was the huge state-directed expansion of military spending during the Second World War.12

When Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy wrote Monopoly Capital in the early 1960s they emphasized the way in which the state (civilian and military spending), the sales effort, a second great wave of automobilization, and other factors had buoyed the capitalist economy in the golden age of the 1960s, absorbing surplus and lifting the system out of stagnation. They also pointed to the vast amount of surplus that went into FIRE (finance, investment, and real estate), but placed relatively little emphasis on this at the time.

However, with the reemergence of economic stagnation in the 1970s Sweezy, now writing with Magdoff, focused increasingly on the growth of finance. In 1975 in “Banks: Skating on Thin Ice,” they argued that “the overextension of debt and the overreach of the banks was exactly what was needed to protect the capitalist system and its profits; to overcome, at least temporarily, its contradictions; and to support the imperialist expansion and wars of the United States.”13

Monopoly-Finance Capital

If in the 1970s “the old structure of the economy, consisting of a production system served by a modest financial adjunct” still remained—Sweezy observed in 1995—by the end of the 1980s this “had given way to a new structure in which a greatly expanded financial sector had achieved a high degree of independence and sat on top of the underlying production system.”14 Stagnation and enormous financial speculation emerged as symbiotic aspects of the same deep-seated, irreversible economic impasse.

This symbiosis had three crucial aspects: (1) The stagnation of the underlying economy meant that capitalists were increasingly dependent on the growth of finance to preserve and enlarge their money capital. (2) The financial superstructure of the capitalist economy could not expand entirely independently of its base in the underlying productive economy—hence the bursting of speculative bubbles was a recurrent and growing problem.15 (3) Financialization, no matter how far it extended, could never overcome stagnation within production.

The role of the capitalist state was transformed to meet the new imperatives of financialization. The state’s role as lender of last resort, responsible for providing liquidity at short notice, was fully incorporated into the system. Following the 1987 stock market crash the Federal Reserve adopted an explicit “too big to fail” policy toward the entire equity market, which did not, however, prevent a precipitous decline in the stock market in 2000.16

These conditions marked the rise of what I am calling “monopoly-finance capital” in which financialization has become a permanent structural necessity of the stagnation-prone economy.

Class and Imperial Implications

If the roots of financialization are clear from the foregoing, it is also necessary to address the concrete class and imperial implications. Given space limitations I will confine myself to eight brief observations.

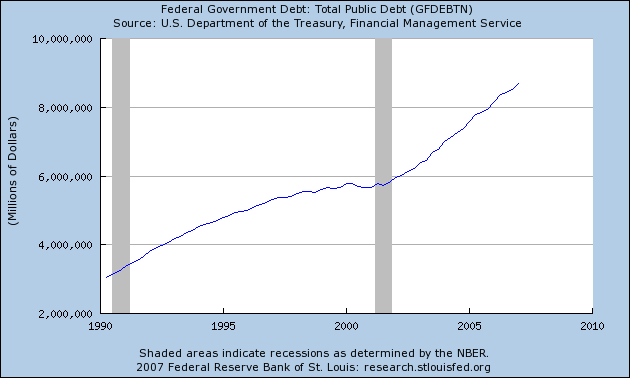

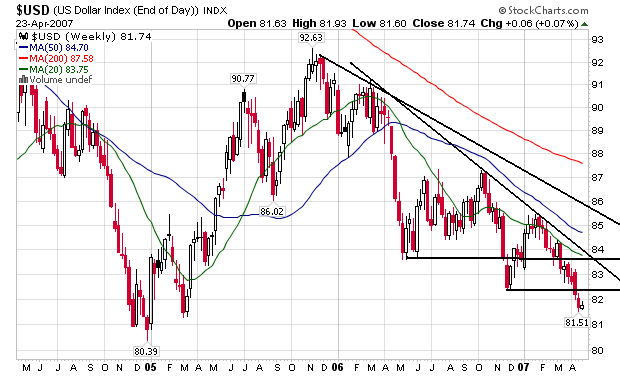

(1) Financialization can be regarded as an ongoing process transcending particular financial bubbles. If we look at recent financial meltdowns beginning with the stock market crash of 1987, what is remarkable is how little effect they had in arresting or even slowing down the financialization trend. Half the losses in stock market valuation from the Wall Street blowout between March 2000 and October 2002 (measured in terms of the Standard and Poor’s 500) had been regained only two years later. While in 1985 U.S. debt was about twice GDP, two decades later U.S. debt had risen to nearly three-and-a-half times the nation’s GDP, approaching the $44 trillion GDP of the entire world. The average daily volume of foreign exchange transactions rose from $570 billion in 1989 to $2.7 trillion dollars in 2006. Since 2001 the global credit derivatives market (the global market in credit risk transfer instruments) has grown at a rate of over 100 percent per year. Of relatively little significance at the beginning of the new millennium, the notional value of credit derivatives traded globally ballooned to $26 trillion by the first half of 2006.17

(2) Monopoly-finance capital is a qualitatively different phenomenon from what Hilferding and others described as the early twentieth-century age of “finance capital,” rooted especially in the dominance of investment-banking. Although studies have shown that the profits of financial corporations have grown relative to nonfinancial corporations in the United States in recent decades, there is no easy divide between the two since nonfinancial corporations are also heavily involved in capital and money markets.18 The great agglomerations of wealth seem to be increasingly related to finance rather than production, and finance more and more sets the pace and the rules for the management of the cash flow of nonfinancial firms. Yet, the coalescence of nonfinancial and financial corporations makes it difficult to see this as constituting a division within capital itself.

(3) Ownership of very substantial financial assets is clearly the main determinant of membership in the capitalist class. The gap between the top and the bottom of society in financial wealth and income has now reached astronomical proportions. In the United States in 2001 the top 1 percent of holders of financial wealth (which excludes equity in owner-occupied houses) owned more than four times as much as the bottom 80 percent of the population. The nation’s richest 1 percent of the population holds $1.9 trillion in stocks about equal to that of the other 99 percent.19 The income gap in the United States has widened so much in recent decades that Federal Reserve Board Chairman Ben S. Bernanke delivered a speech on February 6, 2007, on “The Level and Distribution of Economic Well Being,” highlighting “a long-term trend toward greater inequality seen in real wages.” As Bernanke stated, “the share of after-tax income garnered by the households in the top 1 percent of the income distribution increased from 8 percent in 1979 to 14 percent in 2004.” In September 2006 the richest 60 Americans owned an estimated $630 billion worth of wealth, up almost 10 percent from the year before (New York Times, March 1, 2007).

Recent history suggests that rapid increases in inequality have become built-in necessities of the monopoly-finance capital phase of the system. The financial superstructure’s demand for new cash infusions to keep speculative bubbles expanding lest they burst is seemingly endless. This requires heightened exploitation and a more unequal distribution of income and wealth, intensifying the overall stagnation problem.

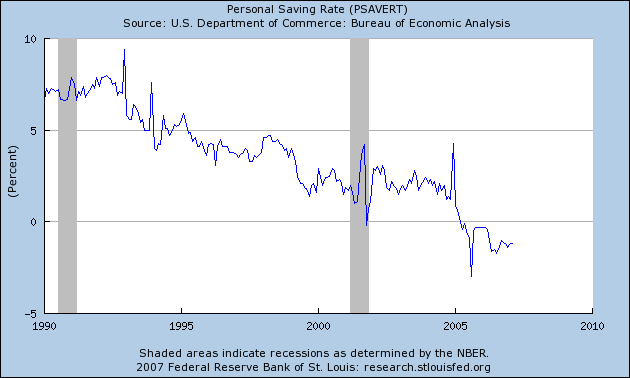

(4) A central aspect of the stagnation-financialization dynamic has been speculation in housing. This has allowed homeowners to maintain their lifestyles to a considerable extent despite stagnant real wages by borrowing against growing home equity. As Pollin observed, Magdoff and Sweezy “recognized before almost anybody the increase in the reliance on debt by U.S. households [drawing on the expanding equity of their homes] as a means of maintaining their living standard as their wages started to stagnate or fall.”20 But low interest rates since the last recession have encouraged true speculation in housing fueling a housing bubble. Today the pricking of the housing bubble has become a major source of instability in the U.S. economy. Consumer debt service ratios have been rising, while the soaring house values on which consumers have depended to service their debts have disappeared at present. The prices of single-family homes fell in more than half of the country’s 149 largest metropolitan areas in the last quarter of 2006 (New York Times, February 16, 2007).

So crucial has the housing bubble been as a counter to stagnation and a basis for financialization, and so closely related is it to the basic well-being of U.S. households, that the current weakness in the housing market could precipitate both a sharp economic downturn and widespread financial disarray. Further rises in interest rates have the potential to generate a vicious circle of stagnant or even falling home values and burgeoning consumer debt service ratios leading to a flood of defaults. The fact that U.S. consumption is the core source of demand for the world economy raises the possibility that this could contribute to a more globalized crisis.

(5) A thesis currently popular on the left is that financial globalization has so transformed the world economy that states are no longer important. Rather, as Ignacio Ramonet put it in “Disarming the Market” (Le Monde Diplomatique, December 1997):

Financial globalization is a law unto itself and it has established a separate supranational state with its own administrative apparatus, its own spheres of influence, its own means of action. That is to say, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the World Trade Organization (WTO)....This artificial world state is a power with no base in society. It is answerable instead to the financial markets and the mammoth business undertakings that are its masters. The result is that the real states in the real world are becoming societies with no power base. And it is getting worse all the time.

Such views, however, have little real basis. While the financialization of the world economy is undeniable, to see this as the creation of a new international of capital is to make a huge leap in logic. Global monopoly-finance capitalism remains an unstable and divided system. The IMF, the World Bank, and the WTO (the heir to GATT) do not (even if the OECD were also added in) constitute “a separate supranational state,” but are international organizations that came into being in the Bretton Woods System imposed principally by the United States to manage the global system in the interests of international capital following the Second World War. They remain under the control of the leading imperial states and their economic interests. The rules of these institutions are applied asymmetrically—least of all where such rules interfere with U.S. capital, most of all where they further the exploitation of the poorest peoples in the world.

(6) What we have come to call “neoliberalism” can be seen as the ideological counterpart of monopoly-finance capital, as Keynsianism was of the earlier phase of classical monopoly capital. Today’s international capital markets place serious limits on state authorities to regulate their economies in such areas as interest-rate levels and capital flows. Hence, the growth of neoliberalism as the hegemonic economic ideology beginning in the Thatcher and Reagan periods reflected to some extent the new imperatives of capital brought on by financial globalization.

(7) The growing financialization of the world economy has resulted in greater imperial penetration into underdeveloped economies and increased financial dependence, marked by policies of neoliberal globalization. One concrete example is Brazil where the first priority of the economy during the last couple of decades under the domination of global monopoly-finance capital has been to attract foreign (primarily portfolio) investment and to pay off external debts to international capital, including the IMF. The result has been better “economic fundamentals” by financial criteria, but accompanied by high interest rates, deindustrialization, slow growth of the economy, and increased vulnerability to the often rapid movements of global finance.21

(8) The financialization of capitalism has resulted in a more uncontrollable system. Today the fears of those charged with the responsibility for establishing some modicum of stability in global financial relations are palpable. In the early 2000s in response to the 1997–98 Asian financial crisis, the bursting of the “New Economy” bubble in 2000, and Argentina’s default on its foreign debts in 2001, the IMF began publishing a quarterly Global Financial Stability Report. One scarcely has to read far in its various issues to get a clear sense of the growing volatility and instability of the system. It is characteristic of speculative bubbles that once they stop expanding they burst. Continual increase of risk and more and more cash infusions into the financial system therefore become stronger imperatives the more fragile the financial structure becomes. Each issue of the Global Financial Stability Report is filled with references to the specter of “risk aversion,” which is seen as threatening financial markets.

In the September 2006 Global Financial Stability Report the IMF executive board directors expressed worries that the rapid growth of hedge funds and credit derivatives could have a systemic impact on financial stability, and that a slowdown of the U.S. economy and a cooling of its housing market could lead to greater “financial turbulence,” which could be “amplified in the event of unexpected shocks.”22 The whole context is that of a financialization so out of control that unexpected and severe shocks to the system and resulting financial contagions are looked upon as inevitable. As historian Gabriel Kolko has written, “People who know the most about the world financial system are increasingly worried, and for very good reasons. Dire warnings are coming from the most ‘respectable’ sources. Reality has gotten out of hand. The demons of greed are loose.”23

Notes

- Gerald A. Epstein, “Introduction,” in Epstein, ed., Financialization and the World Economy (Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar, 2005), 1.

- John Bellamy Foster, “Monopoly-Finance Capital,” Monthly Review 58, no. 7 (December 2007), 1–14.

- The current usage of the term “financialization” owes much to the work of Kevin Phillips, who employed it in his Boiling Point (New York: Random House, 1993) and a year later devoted a key chapter of his Arrogant Capital to the “Financialization of America,” defining financialization as “a prolonged split between the divergent real and financial economies” (New York: Little, Brown, and Co., 1994), 82. In the same year Giovanni Arrighi used the concept in an analysis of international hegemonic transition in The Long Twentieth Century (New York: Verso, 1994).

- Harry Magdoff first raised the issue of a growing reliance on debt in the U.S. economy in an article originally published in the Socialist Register in 1965. See Harry Magdoff and Paul M. Sweezy, The Dynamics of U.S. Capitalism (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1972), 13–16.

- Robert Pollin, “Remembering Paul Sweezy: ‘He was an Amazingly Great Man’”; Counterpunch, http://www.counterpunch.org, March 6–7, 2004; “The Man Who Explained Empire: Remembering Harry Magdoff,” Counterpunch, http://www.counterpunch.org, January 6, 2006.

- Paul M. Sweezy, “More (or Less) on Globalization,” Monthly Review 49, no. 4 (September 1997), 3–4.

- Paul A. Baran and Paul M. Sweezy, Monopoly Capital (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1966).

- James Tobin, “On the Efficiency of the Financial System,” Lloyd’s Bank Review, no. 153 (1984), 14–15.

- In the following analysis I follow a long-standing economic convention in using the term “real economy” to refer to the realm of production (i.e. economic output as measured by GDP), as opposed to the financial economy. Yet both the “real economy” and the financial economy are obviously real in the usual sense of the word.

- Harry Magdoff and Paul M. Sweezy, Stagnation and the Financial Explosion (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1987), 149. Magdoff and Sweezy were replying to an editorial in Business Week concluding its special September 16, 1985, issue on “The Casino Society.”

- Paul M. Sweezy, “Economic Reminiscences,” Monthly Review 47, no. 1 (May 1995), 8; Lukas Menkhoff and Norbert Tolksdorf, Financial Market Drift (New York: Springer-Verlag, 2001).

- The failure of investment banking to regain its position of power at the very apex of the system (as the so-called “money trust”) that it had attained in the formative period of monopoly capitalism can be attributed to the fact that the conditions on which its power had rested in that period were transitory. See Paul M. Sweezy, “Investment Banking Revisited,” Monthly Review 33, no. 10 (March 1982).

- Harry Magdoff and Paul M. Sweezy, The End of Prosperity (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1977), 35.

- Sweezy, “Economic Reminscences,” 8–9.

- This is in line with the financial instability hypothesis of Keynes and Hyman Minsky. See Minsky, Can “It” Happen Again? (Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe, 1982).

- Robert W. Parenteau, “The Late 1990s’ US Bubble,” in Epstein, ed., Financialization and the World Economy, 136–38.

- Doug Henwood, After the New Economy (New York: The New Press, 2005), 231; Fred Magdoff, “Explosion of Debt and Speculation,” Monthly Review 58, no. 6 (November 2006), 7, 19; Epstein, “Introduction,” 4; Garry J. Schinasi, Safeguarding Financial Stability (Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund, 2006), 228–32.

- Greta R. Krippner, “The Financialization of the American Economy,” Socio-economic Review 3, no. 2 (2005), 173–208; James Crotty, “The Neoliberal Paradox,” in Epstein, ed., Financialization and the World Economy, 77–110.

- Edward N. Wolff, “Changes in Household Wealth in the 1980s and 1990s in the U.S.” The Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, Working Paper No. 407 (May 2004), table 2, http://www.levy.org.

- Pollin, “The Man Who Explained Empire.”

- See Daniela Magalhães Pates and Leda Maria Paulani, “The Financial Globarlization of Brazil Under Lula” and Fabríco Augusto de Loiveira and Paulo Nakatini, “The Brazilian Economy Under Lula,” in Monthly Review 58, no. 9 (February 2007), 32–49.

- International Monetary Fund, The Global Financial Stability Report (March 2003), 1–3 and (September 2006), 74–75.

- Gabriel Kolko, “Why a Global Economic Deluge Looms,” Counterpunch, http://www.counterpunch.org, June 15, 2006.