| MSNBC.com |

Special Report

Mark and Kerrie Russo, a Jackson, N.J., couple raising two young daughters, are struggling to hang on. Less than a year after buying a home in 2005, which they financed with a 30-year fixed rate loan based on a solid credit history, a local mortgage broker began sending letters offering to refinance their loan. A new product, the sales pitch said, allowed home owners flexibility to choose from a menu of different payments from one month to the next.

What the broker didn’t explain, Kerrie Russo says, is that this was a “negative amortization” loan — an expanding debt that buried the couple deeper in hock even as they thought they were paying down their mortgage balance.

Like many borrowers who were sold mortgages they couldn’t afford, Russo says that when she called the broker to complain, she was told that because she failed to read the fine print, the responsibility for getting in too deep was hers.

After coming up with about $14,000 to get out of the downward spiral into yet another loan, Russo says she’s learned an important lesson.

“I have learned a new term called 'predatory lending,'” she said. “And that is what I am a victim of.”

As hundreds of billions of dollars worth of these loans “reset” to higher monthly payments, many so-called “subprime” borrowers — historically those with shaky credit histories — are sitting on financial time bombs. They’re finding out the hard way that the paperwork they signed may have buried them under a crushing debt load they can’t sustain.

Swindlers and predators

For some, the lesson learned is: “buyer beware.” But a series of interviews with subprime borrowers, mortgage lenders, appraisers, current and former regulators, and the inspector general of the Department of Housing and Urban Development paints a different picture — of a widespread pattern of questionable lending practices and outright fraud that has already sparked a wave of criminal and civil actions against various players in the $10 trillion market for residential mortgages.

Questionable mortgage practices can take on many forms, but the fall into two broad categories:

As the housing market boomed in the early part of this decade, lenders proliferated with deals that often seemed too good to be true. To be sure, some borrowers - eager to "cash out" their rising home equity generated by the housing boom - were too quick to refinance at below-market interest rates and artificially low monthly payments.

Many of those now facing default and foreclosure failed to do enough homework, relied too heavily on verbal assurances and didn't read the documents they signed closely enough. And not everyone took the bait.

Ron Melancon of Richmond, Va., was among those who stopped short of the brink. When Melancon and his wife went shopping for a bigger house for their growing family a few years ago, he figured he’d have a hard time getting a mortgage. After a rough patch that left him in over his head with credit card debt, he still had a bankruptcy filing on his credit record.

But when he stopped in at a model home in a new subdivision, he was surprised to learn that not only was the builder willing to give him a mortgage, but he was told he could qualify for a loan big enough to buy a $400,000 model, which was bigger and better-appointed than the $320,000 house he and his wife felt their budget would handle. Melancon decided to keep shopping for a less expensive house.

“I just knew from being freshly out of bankruptcy and the experience of going to court and getting your whole life twisted upside down — I just didn’t want to go through it again,” he said. “But it was so hard to back away.”

When he took a closer look at the terms of the adjustable mortgage he’d been offered, he knew he’d made the right decision.

“They never told you the whole truth,” he said. “They said the rate could not adjust more than two points in any one year. But they never told you that the first year out of lock it can go as high as 9.99 percent — it was buried in the paperwork.”

The majority of mortgage professionals that American homebuyers deal with are honest, decent people. But a relatively small group of bad actors has unleashed a wave of fraud and predatory lending over the past several years that threatens to ripple through the wider mortgage market, deepen the ongoing housing slump and crush the finances of countless borrowers who were victims of schemes and abusive practices that have cost them their homes — and their shot at the American dream.

The federal Truth In Lending Act, passed by Congress in 1968 to protect consumers, requires clear disclosure of all terms and costs in lending transactions. That means it’s against the law for a mortgage broker to misrepresent or fail to fully explain all the risks of a new loan — even the risk that interest rates may go up, according to David Berg, a Texas trial lawyer.

“Any promises made, fraudulently, knowing they’re not true, that cause the buyer, the mortgagee, to rely on to their financial detriment is a fraud,” he said. “It can be prosecuted on the state or federal level. But it is a fraud.”

Berg, who says he is getting calls from subprime borrowers who say they were duped, is gearing up to commit “a great deal of our resources” for what he believes “is going to occupy a large portion of our practice.”

“The reliance on false statements is there,” he said. “I think these are good lawsuits and good criminal cases.”

As prosecutors, regulators and Congress begin to unravel the problem, it’s not clear just how widely such lending abuses spread during the height of the housing boom. Because mortgage brokers are regulated state by state, there are no federal statistics on fraud and abusive practice in the mortgage industry. But the number of so-called suspicious activity reports related to mortgage fraud, filed by banks and other lending institutions, more than doubled between 2004 and 2006, according to the FBI, which investigates a variety of financial crimes.

The closest thing to a “mortgage police” is the Inspector General’s Office at the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, where some 650 investigators and auditors are chasing down mortgage fraud and predatory lending cases. In the past three years, they‘ve conducted 190 audits of lenders and brokers, brought 1,350 indictments and won $1.3 billion in court-ordered restitution orders. But it’s not yet clear whether they’ve gotten to the bottom of the problem, according to Kenneth Donohue, who heads the office.

“You almost have to have a crystal ball,” he told MSNBC.com. “Are we looking at the tip of the iceberg or the iceberg itself? It’s too soon to say.”

Rising foreclosures

For many subprime borrowers, the nightmare is only beginning.

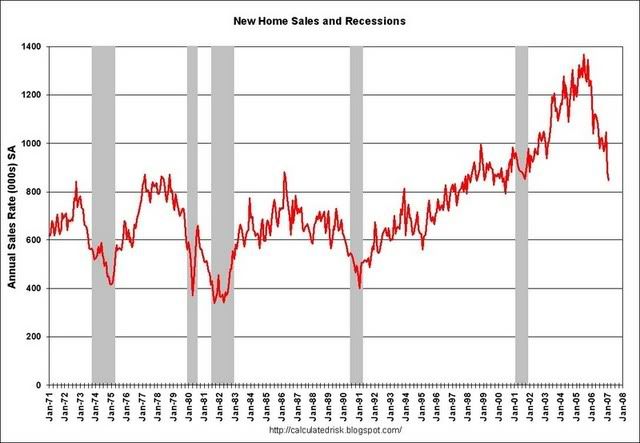

In February alone, some 131,000 foreclosure filings were recorded by RealtyTrac, a Web site that compiles default notices, auction sales and bank repossessions. For all of 2006, the site logged more than 1.2 million foreclosure filings nationwide — or one in every 92 U.S. households, up 42 percent from 2005.

“Based on our numbers for the first two months of 2007, foreclosure activity is running at a rate that would project to a 33 percent increase over 2006,” RealtyTrac’s CEO James J. Saccacio, said in a news release last month. "It appears that as subprime and FHA loans default at higher-than-anticipated rates, and lenders tighten their underwriting standards, we’re going to continue to see a spike in the number of homeowners facing foreclosure.”

These statistics represent the end of a process that is costing many borrowers their homes. A rise in delinquency rates — the number of borrowers who are falling behind in their payments — is a harbinger of more foreclosures to come. From a low in 2005, the mortgage delinquency rate has been climbing steadily and is expected to continue to rise through 2007, according to CreditForecast.com, a joint venture of moodys.com and credit agency Equifax.

And another wave of delinquencies looms, thanks to a newer family of adjustable-rate mortgage products that include “reset” clauses that can raise payments every month, depending on current market rates, and quickly bust a family’s budget. Between the beginning of this year and the summer of 2008, some $650 billion worth of U.S. mortgages — or about 8 percent of the total outstanding — face their first payment reset, according to moody’s.com.

Not all so-called “subprime” borrowers now facing financial problems have bad credit — or at least they didn’t when they originally applied for a loan. In fact, “there is a surprisingly large share of subprime borrowers with FICO scores above 720 (a level consistent with a good credit,)” Fannie Mae chief economist David Berson wrote in a recent commentary.

“What I’m looking at very closely at my firm is the idea of misdirecting a trusting individual toward loans that they don’t need,” said Berg, the Texas lawyer. “I worry about young people who’ve gotten themselves into these adjustable-rate mortgages that are going to be reloaded now at a price they can’t afford. A difference of two points can kill a family’s economics.”

Legitimate real estate and mortgage industry professionals say they are angry and disgusted by the damage done to their businesses by a handful of dishonest players.

“We will tell a customer truthfully if a loan is not good for a customer: ‘We’re not going to do the loan. You will have to go somewhere else,’” said Morris Capouano, owner of Equisouth Mortgage Inc., a lender with 17 employees in eight states based in Montgomery, Ala. “The sad thing is somebody else is going to do that loan. That’s the broker who is concerned about lining their pockets.”

Some real estate appraisers say they've been pressured by mortgage brokers to improperly doctor their reports and inflate the value of a home to increase the chances that a mortgage application will be approved.

“A lot of the smaller guys — the smaller fee shops — they’re very beholden to their clients,” said Diana Yovino-Young, a Berkeley, Calif., real estate appraiser with a family-run business. “So to have even one deal like this go bad — and to basically state the truth — they could lose that client, and that could be 90 percent of their income if they’re a one-person shop.”

One popular tactic among mortgage brokers looking to inflate a home’s reported value is to pitch the job to multiple appraisers at the same time, said Yovino-Young.

“They’ll send out a fax and give you the address of the property and they’ll say, ‘Can you come in at $750,000, say,’” she said. “And the first one who calls back and says, ‘Yeah, that’s doable,’ will get the job. Of course, all of this is completely illegal.”

In some parts of the country, appraisers say, the practice has become so widespread that those who wouldn’t go along saw their business dry up.

"Every day in my office I received threats, attempts at bribes and was told, 'You make this value,' 'We need it pushed,' 'I’ll give you all my business for the rest of the year,'" said Richard Hagar, a Seattle-area real estate appraiser. "(Mortgage brokers) do not want ‘no’ from the appraiser. They start yelling and screaming."

Hagar says the pressure ultimately forced him to find other work in addition to appraising. He now teaches state-approved courses on detecting and preventing real estate and mortgage fraud in Washington, Oregon, and Arizona.

“The fraud problem, it crushed my firm," he said. "I went from 10 appraisers to two. It happened so much, I lost 80 percent of my business.”

Doctoring the documents

In addition to predatory lending, which takes advantage of unwitting borrowers, in some cases lenders were defrauded when entire mortgage applications were faked to trick them into approving loans, said many of those interviewed.

“We have problems with blatant forgery,” said Ed Coleman, compliance coordinator for the South Carolina Real Estate Appraisers Board. “Appraisals are e-mailed to mortgage companies. A mortgage company, if they’ve got the right programs, they can pull a PDF (file). I don’t care if it's protected — they can change it, and they put the signature back on. I’m not computer literate, and I can do it.”

Lenders say these schemes are sometimes difficult to spot: A bogus tax return prepared with a popular tax software package may look just like a real one. On the other hand, some bogus applications are relatively easy to pick out, according to Capouano, the Alabama-based lender.

“It’s hard to prove who did it,” he said. “But if the customer provides W-2s to us and the broker provides W-2s and they're altogether entirely different, then we know there’s a problem here. And we’ve seen that happen.”

Phantom properties

In one recent case in South Carolina, a home seller was accused of doctoring legitimate appraisals of vacant lots by digitally cutting and pasting pictures of completed houses onto loan documents and submitting them to a California lender, which approved the loans, according to Coleman. No one picked up on the problem until an underwriter from the company happened to be vacationing in Myrtle Beach, Coleman said.

“He knew they’d had some payment problems with a few people in (the area),” he said. “So he rented a car and drove over to look at these properties — and they weren’t there.”

In some parts of the country, organized groups prey on first-time homebuyers and other unsophisticated borrowers, the HUD inspector general’s office has found. Illegal aliens, who are enticed into applying for loans with bogus or stolen Social Security numbers, fake tax returns and manufactured employment histories, have become a popular target, according to Donohue.

“They might be approached by a person who asks: ‘Are you renting a place?’” Donohue explained. “They might speak the same language, and the person would share how much they’re paying. And they’d be told, “Well listen, I can put you in a house for half that.”

No money down

Homebuilders who offered easy credit are also playing a role in the unwinding of the subprime market, according to interviews. These builders offer to cover closing costs as a "gift" for buyers with no money to put down.

“So now you’ve got somebody in a house who put no money down and that additional cost that covers that gift rolls into the mortgage,” said Donohue. “But what you’ve done is you’ve artificially inflated the value of those spec houses. And then you give them a very attractive ARM mortgage that’s going to, as we see, accelerate in the next two or three years.”

Industry insiders say that borrowers often were encouraged to take out low “teaser-rate” adjustable mortgages with assurances that after a few years of building a solid payment history, they could refinance at the lower, fixed rate available to those with better credit.

Now, with defaults rising and subprime lenders swamped by bad loans, borrowers who are in over their heads and looking to refinance are seeing interest rates on new loans jumping out of reach.

“But I believe to this moment there are brokers out there who are doing these loans knowing that the rates have changed and they’re not passing it on to the customer until they sign the document,” said Capouano. “You should never have to go to a closing and be surprised, and that’s obviously happening far too much.”

According to mortgage brokers, appraisers and regulators, the roots of the problem date to the mid-1990s, when the market for subprime lending began to take off.

Traditionally, regulated lenders like banks used to make loans directly to borrowers. And those bankers — whose employer’s money was at risk — took the time to understand a borrower's income, job status and the value of the home being purchased.

But much bigger share of mortgage origination has shifted to unregulated, non-bank lenders who quickly resell these loans to investors, where they may ultimately end up in pools of loans that are bundled by Wall Street investment banks, chopped up into securities and, for a fee, sold off to insurance companies, pension funds, hedge funds and other institutional investors.

Unlike banks, many of which are supervised by federal regulators, mortgage brokers are regulated state by state. And state rules and licensing procedures vary widely. In about half the states, a single mortgage broker with a license can open an office staffed by an unlicensed sales staff, according Hagar.

Worse, bad mortgage brokers who are banned in one state can move to another relatively easily — without being detected by regulators in their new home state. Though many lenders maintain their own private databases of bad actors, what’s needed is a national database to track the worst offenders, according to Capouano.

“There should be a national regulation on how to get licensed: You must adhere to certain guidelines and take tests and continuing education and be always knowledgeable,” he said. “That will push these SOB brokers out of the market. “

Reviewing the files

Federal regulations do apply to so-called “conforming” loans sold to quasi-government agencies like Freddie Mac and Ginnie Mae. Loans insured by the Federal Housing Administration, the Depression-era agency set up to manage the world's largest mortgage fund, also carry strict guidelines.

But oversight of those loans has been getting looser, according to HUD Inspector General Donohue. Beginning about a year ago, FHA began allowing approved lenders to keep their mortgage application files on site instead of forwarding them to the FHA, which now spot checks about 6 percent of those applications, he said.

“We live by the review,” said Donohue. “It’s at that point — often we get tips and we have a hotline — but it’s at that point that the referrals are made to us. So if you find a red flag in that loan file, it might take you back to a bad lender. You track it backwards.

“Do I think that a 6 percent review of the total universe is acceptable? You can only imagine how much you might be missing in the process,” he said.

FHA officials declined an interview request from MSNBC.com for this story.

Another S&L debacle?

Some have compared the current wave of mortgage fraud to the savings and loan debacle of the late 1980s and early 1990s, when deregulation of the thrift industry opened the door to widespread abusive lending practices among commercial developers and lenders. After years of trying to roll over bad loans — only to see losses continue to mount – the government finally stepped in with the creation the Resolution Trust Corp. to buy up bad loans. The bill to taxpayers eventually came to $124 billion, according to a 2000 review by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.

So far, no one is suggesting that the total dollar amount of bad loans in the current wave of mortgage fraud will approach that figure. In the savings and loan collapse, commercial mortgages each worth tens of millions of dollars — or more — went up in smoke. Mortgages to subprime borrowers, at the bottom of the real estate ladder, amount to just a few hundred thousand dollars for each borrower.

But the losers in the savings and crisis were largely professional investors, builders and lenders, many of whom escaped with their personal finances intact. Though taxpayers took a big hit, the impact on individuals was relatively small.

This time around, the failures of the residential mortgage market are hitting individuals the hardest. Many are on the very bottom end of the economic ladder, duped by brokers and lenders who preyed on their aspirations to home ownership.

“Because of these few bad apples it is going to affect us, and it’s going to effect the good honest people who really did need this (subprime) program that was available at a reasonable interest rate," said Capouano. “It’s going to push them out of the housing market. It is going to hurt them. And that’s what so sad about all this and so frustrating about all this.

“The (mortgage) industry was trying to create additional home ownership,” said Donohue. “And that’s very nice, and I think that’s a great thing to allow people home ownership. But at what cost? And to what end does that happen? I think what happened is that people — unscrupulous people — took advantage of that and what they did was go out and solicit prospective buyers.”